If you missed parts one and two, check them out.

“I remember you was conflicted

misusing your influence

sometimes I did the same

abusing my power, full of resentment

resentment that turned into a deep depression

found myself screaming in a hotel room

I didn’t want to self-destruct

the evils of Lucy was all around me

so I went runnin’ for answers”

Track 8, (“For Sale?”).

Kendrick is obsessive about his use of voices. On “For Sale?” Kendrick deploys a new voice. This voice is a re-interpretation of Ricky Ricardo, from the television series I Love Lucy. Lamar deploys this voice immediately after his interlude references the “evils of Lucy” and his metaphoric play again riffs off of the pursuit of capitalist gain as mirroring the single-minded pursuit of a lover. “Lucy,” the white female star of the television show, was married to, adored by, and playfully teased by the racial-minority Ricky Ricardo.

Lamar prefaces this song with a reference to the evils of Lucy that surround the speaker, and “Lucy” could also be an abbreviation of Lucifer. To take the TV character and overlay an ambiguous religious abbreviation that could go unnoticed might strike listeners as flippant, but that ‘throw away’ line again highlights the depth of Lamar’s music and interrogation. The song seriously interrogates the pursuit of material goods/gains while enumerating the pitfalls of embracing a ‘gangsta’ personage. Layers and wrinkles abound in this song, and catching all the valences is impossible. Fully unpacking this first verse is difficult: “I remember you took me to the mall last week baby, you looked me in my eyes about 4/5 times ‘til I was hypnotized then you clarified that I (want you). You said Sherane ain’t got nothing on Lucy I said you crazy. Roses are red, violets are blue but me and you both pushing up daisies if I (want you).” Each word, each reference, is volatile. There is the mall, the most material of physical spaces; there are gender norms seeing a female flatter and woo a male until he, hopefully, purchases her something from the mall; then the verse’s biggest collision occurs when Lucy and Sherane wind up next to one another. “Sherane (aka Master Splinter’s daughter)” is a character from GKMC who attempts to leverage her sexuality into an opportunity to murder the song’s speaker. Lust for Lucy, as with lust for Sherane, potentially lead to early demise for the speaker in the song “For Sale?”

The star of I Love Lucy was Lucille Ball, who played Lucy. Naming a character after the actress who portrays her enables a conflation of actor with charact[o]r. That conflation occurs in Lamar’s music when the speakers/protagonists/characters from Lamar’s songs are identified with Lamar (this conflation comes most easily when players in the songs are named Kendrick, as on “Sherane (aka Master Splinter’s daughter)”).

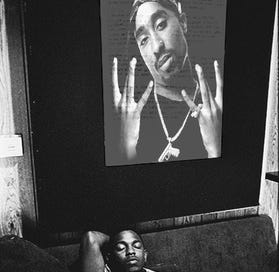

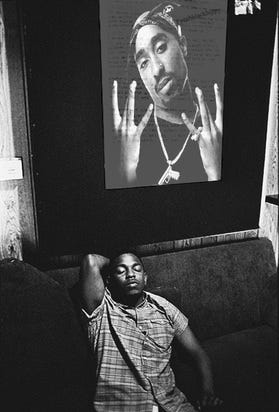

Kendrick’s mastery over his voice-mastery that enables him to portray numerous characters in a single song-can obscure the fact that he is ostensibly always telling his own story. In contrast, Tupac didn’t deploy different voices, didn’t change his delivery, so when he told new stories, or told stories from unique perspectives, they always sounded, literally, like his story. Tupac’s singular voice, when it articulated conflicting perspectives, confused listeners regarding Tupac’s “real feelings” or “real self.” Recognizing the distinction between these two artists, the way Tupac’s singular voice confused listeners into calling him a contradiction and the way Kendrick’s many voices confuse listeners into thinking he is telling other people’s stories, is invaluable in understanding the critical receptions of each artist’s music. Misunderstanding Tupac was so common and was felt so profoundly by critics that eventually Tupac began articulating the visceral rift between his supposed “separate selves” in his own music.

“I remember you was conflicted

misusing your influence

sometimes I did the same

abusing my power, full of resentment

resentment that turned into a deep depression

found myself screaming in a hotel room

I didn’t want to self-destruct

the evils of Lucy was all around me

so I went runnin’ for answers

until I came home”

Track 9, (“Momma”).

Kendrick Lamar distances himself from his personal inconsistencies in ways Tupac did not. One means of distancing Lamar employs in his oeuvre is the creation of an ethos. Lamar creates an ethos in several ways, and to trace that, I must spend some time examining good Kid m.A.A.d. city. A method of ethos creation featured heavily on GKMC-a method that spills over onto TPAB-is his use and re-use of names (Keisha, Tammy, Sherane).

The re-use of names serves a double function; first, it facilitates listener’s entry into Lamar’s ethos by establishing familiarity and metaphorical continuity, and second, it imposes a degree of distance between Lamar and his content. That double function may seem contradictory, but the second move actually enables the first. The distance of the second part of that function arises because listeners hear characters’ “stories” from the narrator who is often telling the story in the third person. Lamar is not explicitly telling his story. This imposed distance moves listeners out of the position of listening to first-person recollections/bragging and into a re-filtered third-person positionality that is shared with the narrator. This move situates listeners alongside the narrator as witnesses to the events of the story. Learning of the events from the perspective of the narrator creates solidarity and an emotional connection between listener and narrator. The distance between Lamar and the narrator is as near or far as the listener desires, and the listener inevitably situates themselves as near or as far from the action as they situate Lamar. Lamar’s distance from the story becomes your distance too.

As well as the subjective distance different listeners envision between themselves and the content, there is the issue of objectivity and authenticity. Is Lamar a fiction writer or a non-fiction writer? What does it mean if Lamar has “made all of these stories up”? I would assert that the distinction is irrelevant because whether the stories happened to Lamar, around Lamar, or were created by Lamar, they are ultimately his. For listeners, the only distance that really exists is the distance between the listeners and the words they hear. If listeners fail to decode, or can summon no impetus for interpreting the lyrics, the distance will be insurmountable. If listeners refuse to acknowledge the potential for authenticity in these stories, then those listeners ignore the fact that the modern world has provided sufficient condition for these realities to come into existence. None of these stories is beyond the scope of the possible.

But the question of what is “real” or “authentic” in rap music is pervasive, and lingers over Lamar’s work in unique and conflicted fashion. This lingering uneasiness over veracity is different in Lamar than in Pusha T, for example, because of the stakes. Lamar has a stake in whether his message is taken seriously in ways that Pusha T does not. Pusha T needs the belief of his fans to ensure album sales. If Pusha T is thought to be lying about his drug-dealing past, or a listener decides that T’s gimmick is bunk, nothing is lost beyond album sales. Pusha T does not advocate for, nor can he in good conscience wish for, listeners to perpetuate the lifestyles-and often the ethics-articulated in his songs. Lamar, on the other hand, who is offering social commentary and speaking like an activist, yearns for listeners to invest in his ethos. For Lamar’s albums to really work, to reach the goals articulated within, empathy and compassion must be must be re-valued and exercised by listeners.

Whether Lamar desires that listeners come to ‘care’ about his music and feel emotionally invested in order to sell more albums and concert tickets or whether he genuinely desires that listeners elevate their consciences through consideration of his music ultimately becomes unimportant. Given the content and the push for mutual respect and empathy, nothing is lost and safety is not compromised if listeners internalize the message of his music. And if they support his music by buying albums and attending concerts, they are supporting a sustainable ethos. If, on the other hand, listeners begin to internalize the morality of Young Jeezy or start to develop a code of ethics based on his music, then society would descend into lawlessness, violence, and drug abuse.

Track 10, (“Hood Politics”).

Kendrick Lamar is a reporter. And Lamar’s reportage reflects his reality, or his experiences, or his beliefs (regardless of whether he is reporting “fact” or “fiction”). Lamar’s reportage gains credence via the ‘truth’ of its many voices, characters, and the resultant diversity of entry points.

good Kid m.A.A.d. city largely reports stories that hip-hop fans have been conditioned to appreciate. The innovation is that Lamar positions the protagonist not as a willing participant out hustling and selling drugs but as a “good Kid” who is forced to reckon with the demons of the “m.A.A.d. city” that he was born in. It is the standard trope of hip-hop, but perfected.

GKMC is hip-hop perfected because, within the album, the tropes of thug, gang-banger, crook, and capitalist pirate, are all on display. Those tropes are all comfort food for the hip-hop connoisseur. Taking those tropes, reporting those voices, then reconstituting them as deterrents to success is the crucial turn that Lamar makes. While those might be comfortable realities, and while he may wish to be hanging with his friends, the peer pressure they exert is not a pressure to succeed but a pressure that will ultimately lead to failure. Lamar considers the parallel of “rap game” as “selling smoke” or selling crack and rather than drop a line about his work as selling smoke, rather than taking a jab at others for selling smoke, he manifests those parallels then inverts them, illuminating the similarities and working against that negative tendency in hip-hop.

“I remember you was conflicted

misusing your influence

sometimes I did the same

abusing my power, full of resentment

resentment that turned into a deep depression

found myself screaming in a hotel room

I didn’t want to self-destruct

the evils of Lucy was all around me

so I went runnin’ for answers

until I came home

But that didn’t stop survivors guilt

Going back and forth, trying to convince myself the stripes I’d earned

Or maybe how A-1 my foundation was

But while my loved-ones was fightin’ a continuous war back in the city

I was entering a new one”

Track 11 (“How much a dollar cost?”).

On GKMC, Lamar describes a youth getting into trouble as a result of peer pressure. That peer pressure is literally the pressure of his friends, while the broader idea of peer pressure articulated is that of Compton peer pressuring youths into gang activity, thieving, and recreational drug use. Or maybe that peer pressure, even more broadly, is the pressure of the “peer” that is the American capitalist system that tells youths-and all people-to get paid. The protagonist on GKMC wavers between a genuine desire to make it “up out this ho alive” as a “legitimate” member of society, and short-sighted desires for fast cash achieved via whatever means are most readily accessible (including, for this good Kid in Compton, criminality).

The pressures from Compton and the United States have commonalities. The overlap, intricately played out, is a theme of GKMC. Lamar examines the interplay of the protagonists, the “good kid” with the “m.A.A.d. city.” Lamar targets the duplicitous community of Compton, USA as his maad city. As a member of that community, the protagonist commits criminal acts with implicit consent from the City that failed to offer the protections that America guarantees citizens.

GKMC is conscious, and it is full of braggadocio, but its braggadocio seems deliberately contrived. That self-conscious braggadocio is crucial to the success of the album. Modern hip-hop appreciates emcees displaying vulnerability, so on "Backseat Freestyle," when Lamar gutturally utters the refrain: “Pray my dick get big as the Eiffel Tower so I can fuck the world for 72 hour,” and later “her body got that ass that ruler couldn’t measure and it make me come fast, but I never get embarrassed,” listeners can appreciate the audacity of the outrageous desire to FUCK THE WORLD, while also sympathizing with a real, human, young man embracing premature ejaculations. Lamar emphasizes collision again in this song because different readings of the word "fuck" see the song potentially spinning 180 degrees. Lamar could simply be a rapper falling in line as he puts out albums that are powered by hit singles that feature popular artists and have videos that invoke institutionalized tropes. For listeners favoring the above reading, the word "fuck" likely reads as a cocky rapper embracing the misogyny that is so prevalent in his genre and wishing to forcibly have sex with as many women as his visibility will allow. 180 degrees from that reading is one which believes Lamar wishes to buck trends and combat the societal problems he enumerates in his music. Listeners who favor the second reading likely hear the word "fuck" as Lamar cursing a world that frustrates, stifles, and stymies him. He may be putting out albums and singles and videos, but he is also undermining the institution in many ways. He could not achieve the platform he has without appeasing the "cosigns" by putting out singles, but if he has to do it, he is also going to sabotage the institution by trivializing it and criticizing it. Lamar is saying fuck THIS world, the one that oppresses and manipulates. His collision is that of a hip-hop artist who knows he has to swing a sledgehammer at the foundation of the pedestal he currently stands on. He puts his livelihood at risk in order to articulate his message.

Bracing herself on an automobile that represents one piece of the conflicted institution of hip-hop, "Sherane" dances on Lamar's right. The depth of Lamar's Sherane metaphor is startling. The reason he builds an ethos around her on GKMC, and again on TPAB, is to force readers to consider "how deep the rabbit hole goes." Sherane is a femme fatale and Lamar's metaphor par excellence. Sherane is the alluring character from "Wesley's Theory" that the speaker desires (though on this song, Sherane goes unnamed). On "Wesley's Theory," the speaker deceives himself, risking victimization by the trappings of a cruel world that collapses emotivities diametrically opposed into a single word, "fuck." The beautiful necessity of reproduction collides with a vicious curse, but the distinction is elided by the singularity of the vocabulary. Lamar is re-parsing those distinctions and charges listeners with acknowledging the complexity of modern humanity. Lamar articulates a siren beautiful enough to lure even those with knowledge of the legendary deadliness. The dancing vixen-appearing two minutes and twenty-eight seconds into the "Backseat Freestyle" video-may make it seem that Lamar is succumbing to the institutional pressures of hip-hop he claims to push against-that he is being misogynistic and contradicting himself-but look again.

The interlude that introduces the section features Kendrick Lamar's actual father smoking weed and crooning to a woman who he desires for her "big ol' fat ass." Lamar's father becomes material for layering of metaphor. Lamar's gluttonous father wants Domino's Pizza, and he wants Sherane. Lamar's father represents the institution of hip-hop, the genre that gave birth-gave its genes-to Lamar's music, style, and flow. The father conceives the son, but what the son does with his inheritance is up to him. Lamar must embrace the legacy of hip-hop/father because history must be acknowledged, but he is also charging listeners with reconsidering past and present.

Consider what is being presented after the interlude. Sherane dancing next to a car while Lamar stands motionless, is the most gripping image from this video. The image lingers in viewers' memories just as it lingers on the screen longer than any other image from the video. Now watch Lamar through that sequence. Lamar is staring at you, the viewer. Lamar is thinking about his audience, not the 'object' of the video. Lamar never looks at Sherane, but I bet you did. If you thought Lamar was being a chauvinist pig, that is because you that brought that reading to the video. You are caught in the trope of hip-hop and the media cycle that reads hip-hop through a veil, seeing only certain aspects of the music and often through a dim haze of negativity. The Sherane sequence in the video lends a visual to the metaphor embedded in the word "fuck." Maybe Lamar wants to have sex with the woman next to him or wants viewers to want to, maybe he is saying fuck the assumptions of a society that would misrepresent his music, his message, and sexuality. After all, it is you who is staring at Sherane's butt, hardly noticing Lamar as he watches your transfixion.

good Kid m.A.A.d. city has moments of vulnerability, it deploys complicated story-telling, it has profound interludes that provide entree into Lamar’s life and its use of voices speaks to a culture of “ADHD” that wants more everything, only to see the many voices harmonize and form a singular ethos. With part of that ethos harkening to Tupac's aesthetic via clarity, braggadocio, and thuggishness.

The album traces the arc of a youth trying to impose himself on his life, a youth trying to come out of the tunnel of a troubled city with not only his life, but some money, a foundation, and a foot in the door of American capitalism. Though the youth experiments with criminality and gang-affiliation, his experiences with them are like his first experiences with marijuana: “Cocaine laced in marijuana and they wonder why I rarely smoke now. Imagine if your first blunt had you foaming at the mouth.” Those bad first impressions (with both drugs and criminality) lead him on an arc that culminates, in time-bending fashion, in the album listeners are already enjoying. The protagonist escapes the pitfalls of criminality and learns how to convert those experiences into a “legitimate” occupation as a rapper. The album is testament.

Perhaps GKMC had a positive reception because in all those voices, listeners could hear a community, could hear themselves.