As Isaiah Rashad is from Chattanooga, Tennessee and I am from Maui, Hawaii, it was unlikely that our paths would cross.

As Isaiah Rashad is a rapper from Chattanooga, Tennessee and I am a surfer from Maui, Hawaii, it was unlikely that we would have much in common.

Rap is my favorite music.

Isaiah Rashad rips rap.

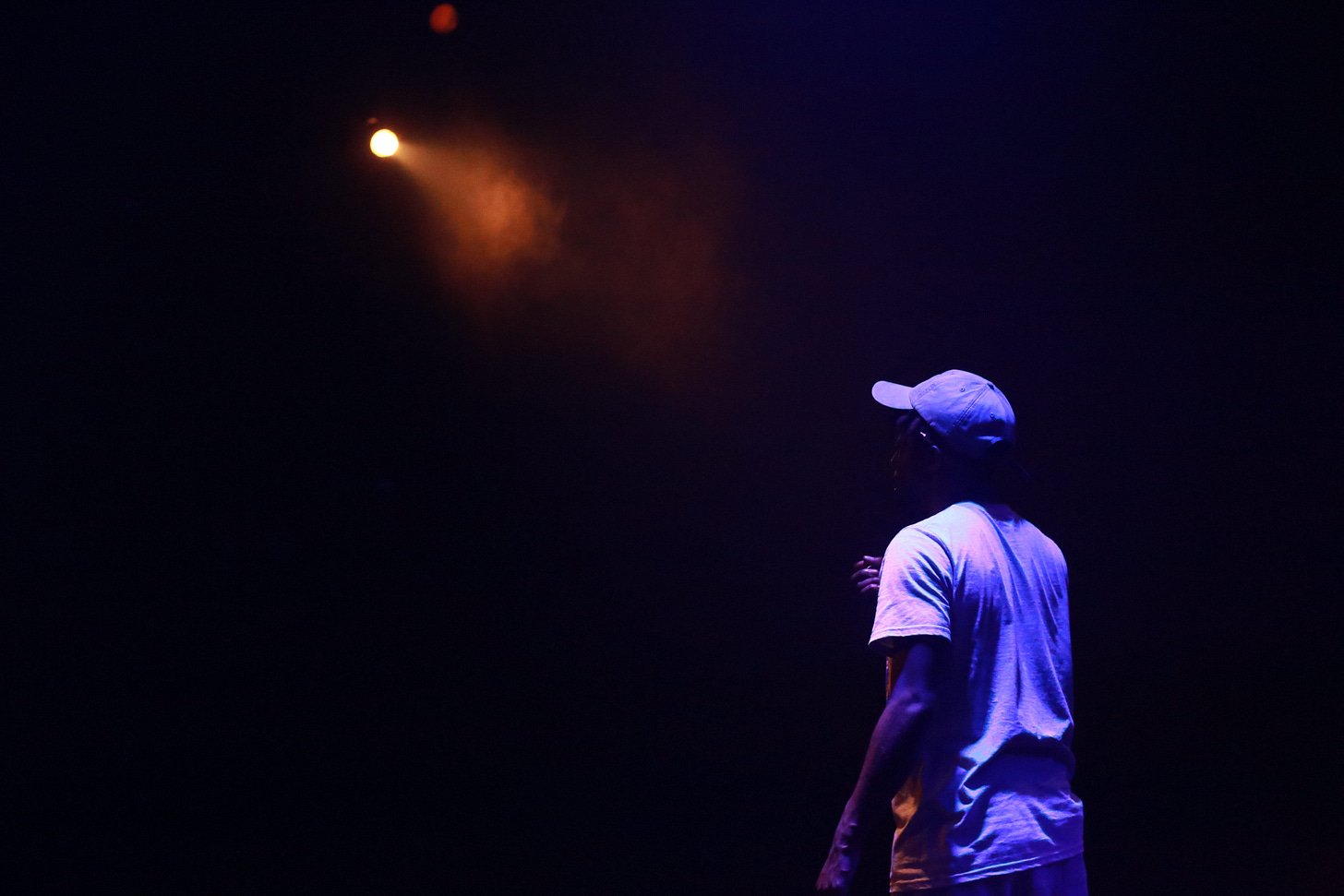

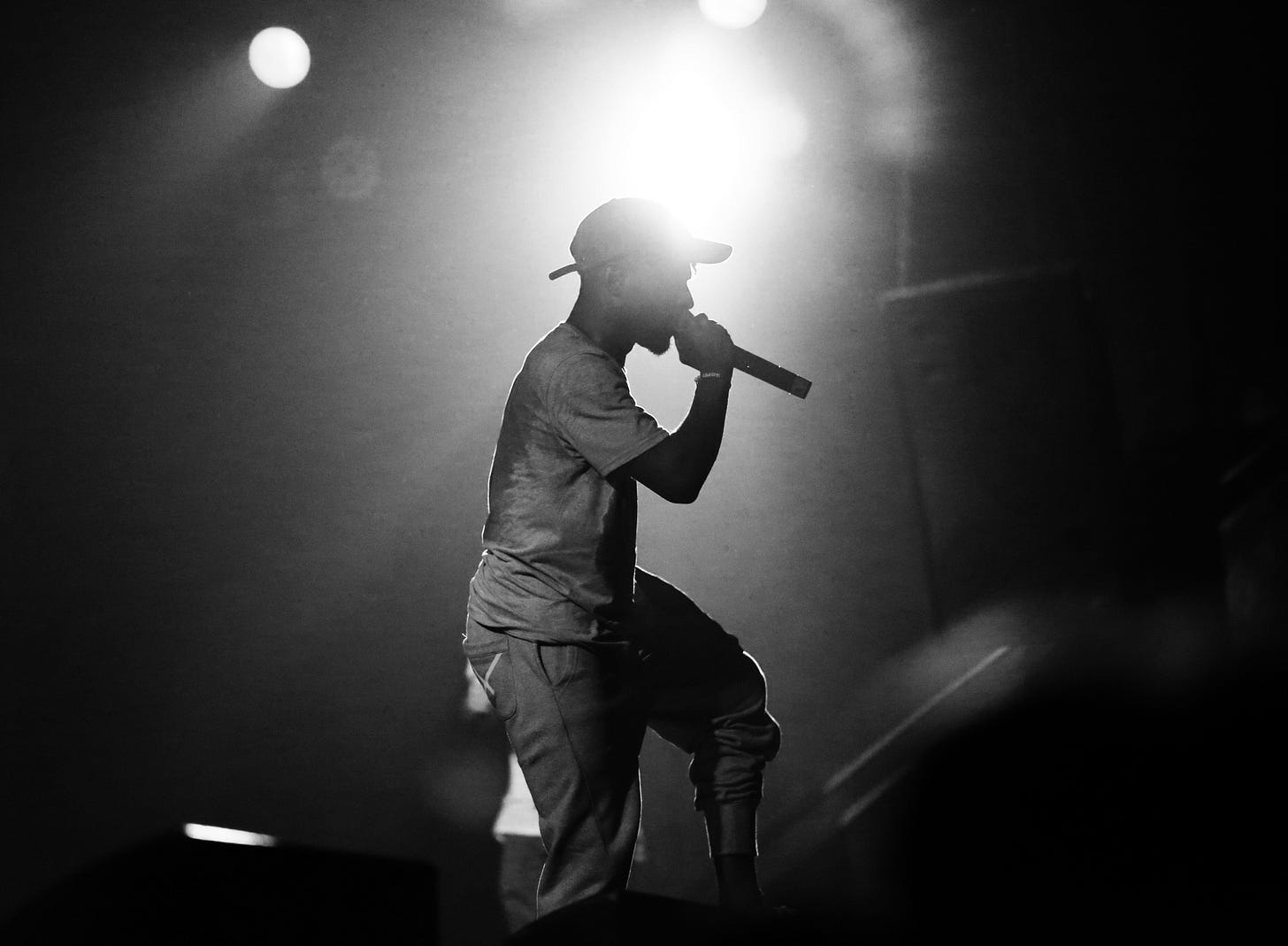

San Diego is a city that I wouldn’t want to live in but where, hoping to surf often, I attended college. I recently went to an Isaiah Rashad concert in San Diego as part of the Lil Sunny Tour. Here are some of the things that occurred to me while watching that show: Isaiah Rashad has long arms; Isaiah Rashad is better live than on his impressive albums; when Isaiah, the live version, goes a cappella, it is fantastic; Isaiah has a gravelly, decidedly human voice but he can send the gravel register to the background, catch a melody, and throw some gnarly croon-shred down on his hooks (or hooks sung by SZA on his albums); he was wearing cutoff jean shorts, a dark-blue long sleeved shirt that read “injury” in wavy red writing on the back and resembled a novelty Lifeguard shirt from Mission Beach, with an adjustable denim hat and some fresh sneakers; my step father and I were partners while I worked construction and one day I was at my mom’s house and he was wearing cutoff jean shorts and I told him they were dope so the next time I saw him, he made me a pair; Isaiah’s jean shorts look like mine.

Isaiah Rashad is adept at sensing when the crowd is gonna catch his groove and ride with him, so just at that moment, when your head is down and you are totally in his music with him, he makes his hat disappear and his short dreads start whipping around like sea anemones in a tide pool during a tropical storm. At the end of the San Diego show, he came downstage right and started taking photos with the crowd and I was standing near the rear because I’m a surfer and I like my space. From my vantage, I was thinking about the chroma of the San Diego hands that were reaching for him and, based on the makeup of the audience, I knew that the gross majority of those hands were male and I returned to a question I always consider at concerts. The question probably plagues me during such moments because I grew up on Maui where there aren’t big shows (Mayjah Rayjah aside) and I don’t know as much about how to be in a crowd as people who grew up in San Diego or Los Angeles might.

That question, three ways, is: “Do I belong here?” or: “How do I belong here?” or: “How do I fit here?” which I guess is not a novel thing to wonder. It is apparently the quintessential human question: “Why am I here?” But maybe it’s a human question that arises when we start constituting ourselves in relation to the large swath of flesh called humanity. The dearth of crowds was unique to growing up on a rock in the Pacific with 200,000 people spread thinly. With surfing as a primary distraction, I sat among the waves, as far from crowds as I could get, and I wondered often, but never about my place.

When I was in college, there was a San Diego bar called Cass Street Bar and Grill. It is on Cass street and when I visited, the male portion of the crowd tended to have sun-bleached hair, tended to wear Vans , tended to have slim pants sitting on their waists as well as a surf apparel brand of shirt. When I visited, I dressed in extremely baggy pants with a much too large waist that sat below my butt, clean sneakers, XXL or XXXL T-shirts with loud patters, and a close buzz cut. I knew the other men there probably thought of themselves as surfers. I also knew they looked the part more than I was willing to. I had some of my most profound identity crises in Cass Street Bar and Grill. Why was I at that bar? Why was I in San Diego? I felt with a punishing severity that I did not belong. I also felt that if I would just suck it up and wear different clothes I might at least look like I belonged. As a surfer, though, I felt that if I would just wait out the lull, a swell would arrive and I would be ready when it came.

Isaiah was scheduled to perform another concert less than a week later in Oakland, at The New Parish. The day of the Oakland concert, a friend from my high school on Maui texted me with tickets. A few hours later, my friend and, I along with a couple of photographer friends, also Mauians, stood in a carpeted lounge area with camera equipment on the floor. Next to the equipment were two couches hosting comfortably seated rappers and their entourages, all encircling a broad coffee table, and against the opposite wall stood a table with water and snacks, as well as a grey sliding door leading to a teensy bathroom.

Just to the right of the bathroom there were three stairs that led to a rooftop patio where there was a porch rimmed with benches and from which the opening acts could be heard. I chatted in the living room a bit before walking out to the patio.

Emerging, I immediately saw Isaiah Rashad taking his arm from around my friend’s waist, where he had placed it for a photo taken by one of our photographer friends.

Unsure of how to react, being just several feet from Isaiah in such an intimate setting, I recalled one of Isaiah’s pre-show rules: “Show respect and give people their space, because everyone is here for different reasons. Some people wanna sing along, some people wanna dance, some people wanna drink, some people wanna smoke, and some just wanna chill.” In the same moment that I knew this was the right way to behave, I also recognized that this is also a rule of surf lineups.

On the rooftop patio, I talked with friends, admired the views, soaked up the warm spring evening with a nearly-full moon relaxed overhead, all while Jay IDK, Hugh, and other personalities roamed. Isaiah chatted with nearly everyone on the patio, and I wasn’t gonna snake any of those people to go say something corny. I patiently waited for my wave. Still, I got antsy, finally looked around for him and hopefully a conversation opening, only to realize that Isaiah had already left.

Jay IDK was going on soon, so my friends and I decided to go downstairs to watch/photograph. En route, we had to walk back into the lounge, and Isaiah’s manager was in front of the door talking to Isaiah, who was at the bottom of the three patio steps, which meant I had to walk through their conversation to get into the lounge.

The photographers pushed through the door, but I got waylaid because the manager, who had auburn hair corn-rowed into long braids that fell down his back over a customized satin varsity jacket with bulldogs and TDE embroidered on the back, looked mean and I didn’t want to ask him to move. Waiting, I noticed that Isaiah was holding a Big Daddy pickle in a bag. As Isaiah finished the conversation we had just walked through, I lingered another second. Suddenly Isaiah struck a Tae Kwon Do stance. One hand balled into a fist held palm up at his waist, his other hand fiercely, yet cautiously, held the already opened pickle in front of him, lest the juice leap from the bag, and it acted as an extension of his ready stance, a stance he just as suddenly broke out of in order to sardonically side-kick the door shut as if to say: "stop interrupting my shit, Door!"

In this moment of levity, I offered my first words to Isaiah: “Are you just working a giant pickle right now?”

“I’m ‘bout to be,” he responded, answering my question but ignoring the question I was thinking, which was whether the pickle was part of his pre-show routine. Then he continued: “You know what’s better than a pickle? A tomato with salt and pepper.”

“Just a whole tomato?”

“Yeah.”

“I can’t do a whole tomato. I could get behind a pickle though…”

“I’ve always liked pickles. Like, when I was a kid, we’d be sitting on the couch and all the other kids wanted chips and shit, but I would just have a pickle, or a tomato, or a pepper, or something.”

Isaiah’s albums are best rendered through the metaphor of surfing. During a good session, I catch quite a few waves. While each is exciting in its own way, I could never narrate each one moment by moment. I get lost in the adrenaline and excitement. Sometimes you catch a smaller wave that amplifies as it goes along, adding height and length, becoming a long, fun ride with several hacks. Then, as you’re paddling out, you catch another that’s the same size and looks similar but closes out so you paddle out again, sit and wait for a set by meditating, suddenly you catch a bomb, pull into a little barrel, come out, smack the lip, and kick out. But in real-time, you just caught three waves in seven minutes and repeating that multiple times over a two hour session means it quickly becomes challenging to keep the number, quality, and sequence of rides mapped in a linear, temporal fashion. Afterwards, I always wish I could have stayed out longer and that the waves could be as good as the best waves of the session forever without pause. Isaiah’s songs tend to lack conventional hooks, leading to titles that are remarkably un-self-evident. Rashad also experiments with duration, false endings, and meticulously blended continuing non-restarts.

Every song on Cilvia Demo and The Sun’s Tirade is good. “Park” is a rapper’s rap song, and performed live it becomes a rollicking punk rock anthem. “Park” is the set wave where you get barreled, come out to whack the lip with abandon, then as you kick out, you realize four people are paddling out and bore witness to your fury. “Rope” is the mid-sized wave that seems to get bigger as it goes and is remarkably section-y, yielding ample space for improvisation: cutbacks, snaps, blown-out gouges into the lip and an inside air section. “Heavenly Father” is a meditation between waves as you see the flicker of a swell on the horizon.

I didn’t take a picture with Isaiah. I didn’t tell him my name and never had him tell me his. I didn’t tell him how good I thought his shows were. I didn’t tell Isaiah I once tweeted at him hoping to get liked or re-tweeted so I could feel validated, hoping to be constituted as “fitting” into his worldview. He the lone god capable of granting entry to the universe created in his music. Instead of doing or saying all that I might have, I let myself be a surfer. I rode the swell, organically had a handful of conversations, saw him with his people, heard him tell funny stories with them, and left without saying goodbye.

A few days out, I think I know why. He has already validated my life-experience with his music and I needn’t ask more of him. Isaiah Rashad may be from Chattanooga while I’m from Maui, and I may never get to ask if he has ever gone surfing, but I don’t need to. He has the spirit of a surfer. I hear it in his music, I see it in his style, I saw it in person, and whether he knows or not, I know more about who I am because of him.